US Has Long History of Restricting Immigrants

Last Friday, President Donald Trump signed an executive order banning refugees and people from seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the United States.

The countries are Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen.

Protesters across the U.S. immediately objected to the restrictions. Some argue that Trump’s order discriminates against Muslims and defies the American tradition of welcoming immigrants.

Many of these protesters correctly point out that the U.S. is a country of immigrants. However, history shows that the U.S. is also a country of restrictions on immigrants.

Trump’s government is not the first administration to restrict immigration, including on the basis of national origin.

Restrictions on Asian immigrants

The U.S. Constitution, which went into effect in 1789, gave Congress “absolute authority” over immigration law, says Linda Monk. The president executes those laws through regulations.

Monk wrote a book about the Constitution called “The Words We Live By.”

She explains that for about the first 100 years of American history, Congress did not place any federal limits on immigration.

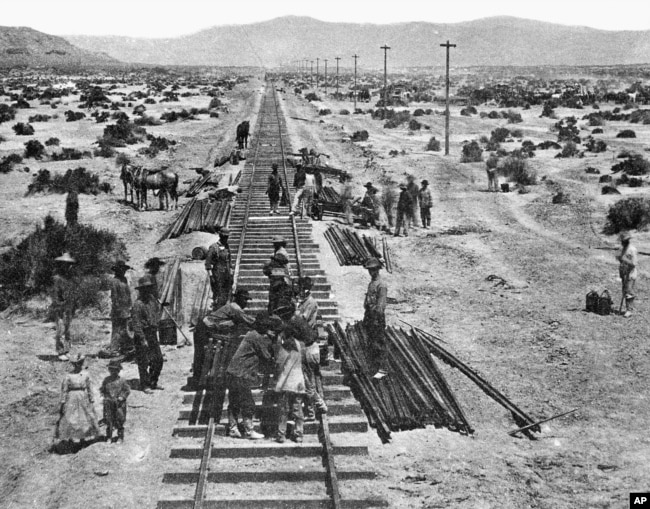

During those years, Irish and German immigrants came to the U.S. in large numbers. Many Chinese immigrants did, too. They hoped to find gold in California and then, when they did not, they stayed anyway.

But some members of the American public disapproved of these groups. They did not like the Catholic religion that many Irish and Germans immigrants practiced. And they did not like Asian immigrants, whom they viewed as convicts, prostitutes, or competition for jobs.

So, in the late 1800s, Congress moved for the first time to limit the number of immigrants. Lawmakers targeted Asians, especially Chinese. The Page Act and the Chinese Exclusion Act banned most Chinese women and workers.

Restrictions on other nationalities

By the turn of the 20th century, the U.S. federal government had increased its role in immigration. It established Ellis Island in New York as the entry point for immigrants. And it oversaw a dramatic increase in the number of immigrants, especially from Italy and Eastern Europe. Many of the new arrivals were uneducated and had little money.

Once again, some people opposed the number and kind of immigrants entering the country. A group called the Immigration Restriction League was formed. They petitioned Congress to require immigrants to show that they could at least read.

Both Presidents Grover Cleveland and Woodrow Wilson opposed the requirement. But in 1917, Congress approved the measure over Wilson’s objections. People who wished to settle in the U.S. now had to pass a literacy test.

In the 1920s, restrictions on immigration increased. The Immigration Act of 1924 was the most severe: it limited the overall number of immigrants and established quotas based on nationality. Among other things, the act sharply reduced immigrants from Eastern Europe and Africa. And it completely restricted immigrants from Asia, except for Japan and the Philippines.

At the same time, the historian’s page at the State Department notes that the act made more visas available to people from Britain and Western Europe.

“In all of its parts, the most basic purpose of the 1924 Immigration Act was to preserve the ideal of U.S. homogeneity,” the State Department history page concludes.

Major change in U.S. immigration policy

During the 1940s and 50s, the U.S. made some policy changes that increased – however slightly – the number and nationalities of immigrants.

Then, in 1965, a major change happened. Under pressure in part from the civil rights movement, Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act. President Lyndon Johnson signed it.

The act eliminated the quota system based on nationality. Instead, it prioritized immigrants who already had family members in the U.S. It also sought to offer protection to refugees from areas with violence and conflict.

Even though the act kept some limits in place, the origins of immigrants changed dramatically. Instead of being from Western Europe, most immigrants to the U.S. by the end of the 20th century were originally from Mexico, the Philippines, Korea, the Dominican Republic, India, Cuba and Vietnam.

So, what about Trump’s order?

A professor at the University of Miami School of Law says the 1965 law ended “overt discrimination” in U.S. immigration policy. Kunal Parker is also the author of a book called “Making Foreigners: Immigration and Citizenship Law in America.”

Parker says that people who are protesting Trump’s executive order probably “perceive what is happening as contrary to U.S. tradition since 1965.”

But Parker cautions against seeing Trump’s action as illegal. He points out that the Supreme Court has historically permitted the president and Congress a good deal of authority to regulate immigration.

And, he notes, President Obama also signed an executive order related to immigration. That order aimed to protect the families of undocumented immigrants with U.S.-born children.

However, Parker says, “Something that is legal might be very problematic.”

Both Parker and legal scholar Linda Monk also note the Constitution requires both Congress and the president follow certain procedures when regulating immigration. Those procedures protect against discrimination.

“The highest law says that these actions have to be carried out fairly,” says Monk.

___________________________________________________________

Words in This Story

executive - adj. an order by the president

origin - n. the point or place where something begins or is created

petition - v. a written document that people sign to show that they want a person or organization to do or change something

quota - n. an official limit on the number or amount of people or things that are allowed

slightly - adv. n a very small amount or degree

eliminate - v. to get rid of something

overt - adj. obvious