[Us and Them] ‘We are here,’ say LGBT Koreans but so is the hate

Education and politics play important roles in changing perspectives, gay politician says

|

|

|

From the most mundane of activities to larger goals such as being widely accepted by society, the lives of sexual minorities in South Korea are fraught with difficulties.

“I don’t go to a hospital unless it is known as being queer-friendly. Usually I just don’t go to hospitals,” said Jung-hyun, who is currently transitioning to male. Jung-hyun, a pseudonym, says the mismatch between his male appearance and female gender on official documents leads to strange looks and questions at most hospitals.

While his family and colleagues have accepted him the way he is, bias and hate toward sexual minorities are still the norm in Korea.

“Listening to hate from people who claim to know about sexual minorities, often the case is that they knew nothing (about sexual minorities). Despite not knowing, often they don’t want to find out or listen,” he said.

“Being a sexual minority is just one of many characteristics a person has. See us as just another person.”

Faced with ignorance and open discrimination, activists use platforms such as the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia, or IDAHOT, which falls May 22, to call for equal rights.

Along with the Seoul Queer Culture Festival, IDAHOT is one of very few platforms for sexual minorities in Korea, who say they face “extreme hatred” on a daily basis.

This year IDAHOT’s slogan was “We are here,” which activists say embodies their desperation. Desperation to rid society of discrimination and prejudice, desperation to live out their lives as they are, and desperation to fight against exclusion and punishment.

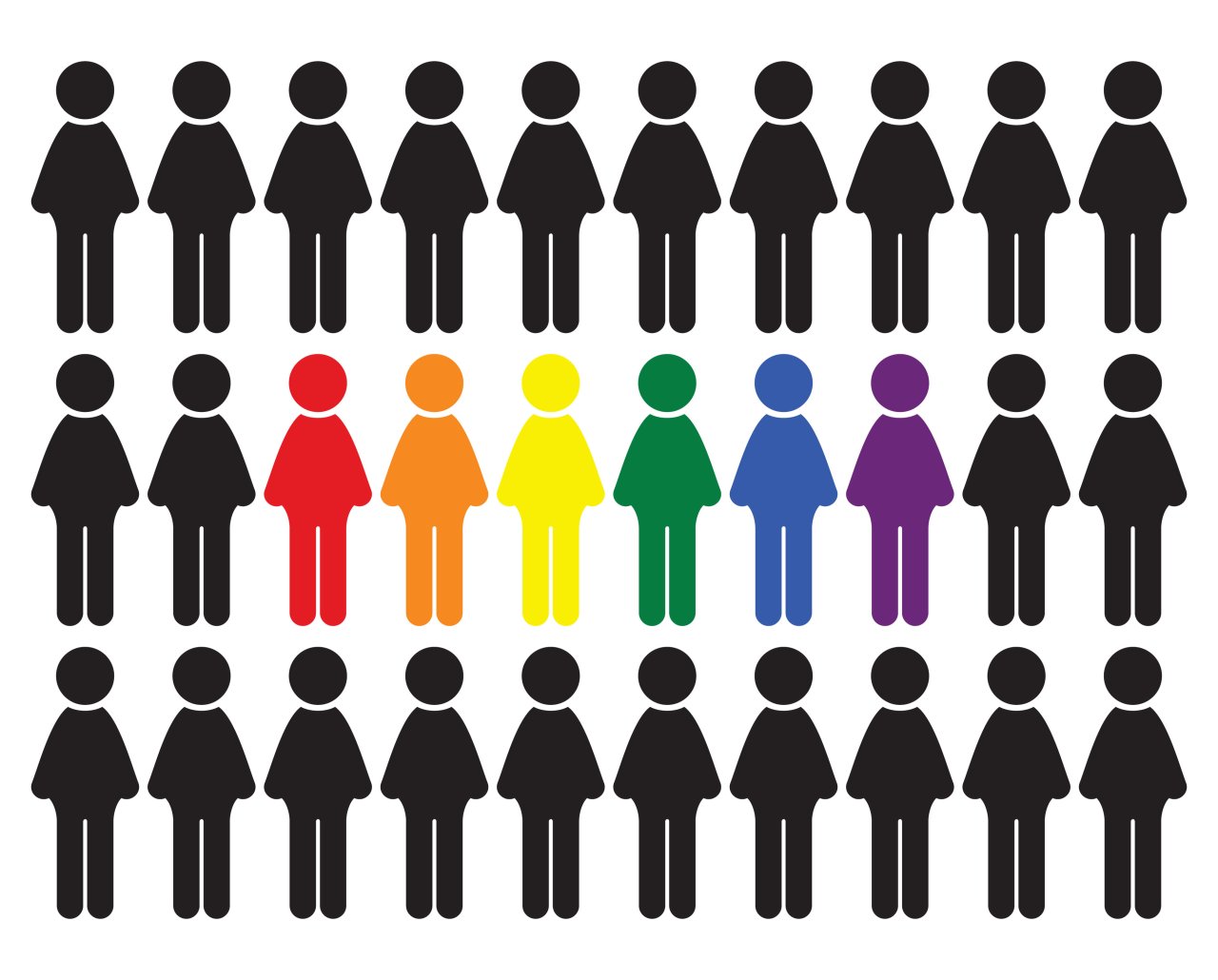

Despite activists’ efforts, awareness is lacking. According to a social integration survey by the Korea Institute of Public Administration in 2020, almost 6 out of 10 respondents said they could not accept sexual minorities as part of society.

“Because sexual minorities are not considered as our neighbors, we are not free from ignorance, discrimination and hatred,” said Oh Seung-jae, spokesperson for the Youth Justice Party, who is openly gay.

“Two areas education and politics each play an important role,” Oh said. “In order to change perspectives, proper education to take out bias and consider sexual minorities as normal people is needed across all sectors, including public education.”

Pointing to the example of Taiwan, which became the first Asian country to legalize same-sex marriage in 2019, he said human rights education was one of the major factors in bringing about legislative change. In contrast, Korea’s National Assembly has yet to pass a proposed anti-discrimination law despite years of advocacy.

“I think if you help make social changes with pride from wherever you are, it would be more helpful in bringing us closer to a society where it is not difficult to reveal anyone’s sexual orientation and no one is discriminated against for being a sexual minority,” Oh added.

Open discrimination

While the efforts of activists and policymakers are having some impact, discrimination continues unabated.

According to a study published in the Journal of the Korea Contents Association in 2018, until the late 1990s the media depicted sexual minorities as abnormal or perverted, representing them as the main culprits in the spread of AIDS.

Since that time the media’s portrayal of sexual minorities has changed, but now they are depicted as consumers who have chosen a particular lifestyle and are not open about it. This, some experts say, could further isolate them.

“In the space of media, sexual minorities are represented as possessing distinctive tastes, such as in the stereotype of ‘sophisticated gays,’” Kang Oh-reum wrote in an article published in 2015 in the Seoul National University journal Cross-Cultural Studies.

“Based on these ideas, media often represent sexual minorities as creators of new products, or as people whose individual preferences we must be considerate of.”

Some Christian churches do little to hide their prejudice.

The Korean Methodist Church, one of the largest Protestant groups in the country, amended its rules in 2015 to clearly oppose any action that condones homosexuality. Last October the group suspended the Rev. Lee Dong-hwan for two years for saying a prayer of blessing during the Queer Culture Festival in Incheon in 2019.

Despite the efforts of lawmakers to pass a law that would prohibit discrimination against LGBT people, so far it has failed every time due to backlash from some conservatives and churches. One such bill met the same fate in June last year, but a new version has since been introduced and many observers say it has a good chance of passing.

“We believe that the ultimate purpose of trying to make the equality law is to allow homosexuality and legalize same-sex marriage,” the Communion of Churches in Korea said in a statement in response to the proposed equal rights law.

“Christianity opposes all discrimination and hatred. That is the teaching of the Bible. But homosexuality is an abominable sin of denying God.”

Small changes

But changes are happening in the educational system, just as the latest anti-discrimination bill is gaining momentum at the National Assembly.

The Seoul Metropolitan Office of Education announced a comprehensive plan in May to protect students’ human rights. In a first for an official written plan, it specifically mentioned the need to support LGBT students and protect them from discrimination and hatred.

Since the announcement, conservative parents’ associations and civic groups have carried out relay protests in front of the education office denouncing the decision.

“The fundamental spirit of the students’ human rights plan is that all students should be respected without any discrimination,” an official from the education office said.

“There have been constant reports of sexual minority students’ struggles, so we decided to take a step forward to protect them.”

In March, Yoon Hyun-bae, a professor at the Seoul National University College of Medicine, began offering the country’s first medical school course on sexual minorities’ health rights and medical concerns.

“As the course became better known among students, four senior students came to me and asked if they could participate in practical training (on treating sexual minority patients) with me over the summer before they graduate,” Yoon said.

The professor explained that many LGBT people face a lack of access to health care as many medical workers lack professional knowledge or skills, and sometimes they are not friendly toward LGBT patients, adding that Korea was quite late in adopting this type of education.

“I had a few chances to talk about the teaching experience at academic conferences attended mostly by medical school professors. There, other universities showed a lot of interest, which got me thinking that (medical education on sexual minorities) can be carried out in other schools,” Yoon said.

“I tell teachers that young students have lots of interest in the subject and want the education, so we should live up to that.”